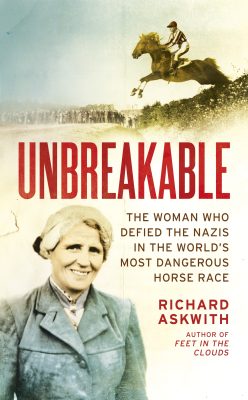

Martin Cáp's interview with the author of UNBREAKABLE

To mark the publication of Richard Askwith’s book UNBREAKABLE on March 6th, Martin Cáp posted an interview with the author on www.jezdci.cz. Questions asked by Martin Cáp, answers by Richard Askwith. Martin’s “original” Czech-language version of the interview can be found under http://www.jezdci.cz/clanky/zesmesnila-tvrde-chlapy-i-nacisty-rika-autor-knihy-o-late-brandisove/.

Martin Cáp is a leading historian of Czech racing, a leading writer on Czech racing, a top presenter and expert on racing on Czech Television, and also top presenter and announcer at several of our racecourses. The English version is in fact the original interview, which Martin adapted slightly for his translation into Czech.

You are not a 100% racing man. Did you have any interest in horse racing before this?

I’ve been moderately interested in racing all my life, but apart from a few years in my twenties when I became a bit obsessed by it, it’s always been a very casual interest. And what little expertise I do have relates to flat racing rather than steeplechasing. So I approached the story of Lata Brandisová and the Velká pardubická as an ignorant outsider. But sometimes, I think, that can be a good starting-point for an author.

After your Emil Zátopek biography, you returned to another Czech topic. Was this a coincidence, or had you had Lata's story in your mind for a longer time? When and how did you stumble across the name Lata Brandisová for the first time?

I had never heard of Lata Brandisová until several months after my Zátopek biography was published. I’d been trying to learn Czech while I was working on that, but I hadn’t made much progress, so I carried on trying to learn the language when I got home, listening to Czech radio and Czech podcasts and things like that. And at some point in late 2016 I heard a very short item about her on Český rozhlas. That fascinated me, and I tried to find out more, although initially I had no plans to write about her. But the more I found out, the more I wanted to find out even more. Her story seemed to cry out to be rescued and told – and before I knew it I had embarked on writing her biography.

What was it in the Lata Brandisová story that was the most interesting thing for you at the beginning?

I think it was the idea of two different kinds of courage converging: on the one hand, the courage to ride over Pardubice’s life-threatening jumps; on the other, the moral courage to face down all the prejudice and intimidation that she faced as a woman. She must have been a remarkable human being, and from the moment I first heard her story I wanted to find out more about her. I still do…

This really is an attractive movie-like story, but there are many specific details. Are we, as people of the 21st century, able to fully understand Lata and her aspirations, or is there something in the story that can get "lost in the translation", in your opinion?

In some respects, the world has evolved so much that it is difficult for us to see things through the eyes of Lata and her contemporaries. For example, attitudes to the welfare of animals were very different in those days – although if there was one person whose gentle, compassionate approach to horses would be in tune with modern values, it was Lata. Similarly, it’s hard for any of us to see the world through the eyes of super-rich aristocrats such as the Kinský family (who feature a lot). But I’ve tried to provide readers with enough context and enough sense of perspective to make their own adjustments – just as they would adjust their judgements to allow for the fact that Lata spent much of her life under Nazi or Communist rule, but we don’t.

What perspective did you choose for telling Lata's story?

For me it’s not just the story of a woman. It’s the story of a nation, idealistic but doomed. And it’s the story of an age, not unlike our own, in which some very noble ideals – liberal democracy, gender equality, political tolerance – were coming under attack from extremists of many kinds, and good people were bemused about what they could do about it. I’ve tried to tell the story in such a way that all those themes feed off each other and shed light on one another. So the Velká pardubická isn’t just a sporting contest, in my telling: it’s a battle of values.

Are there any story lines, or details, that didn't make it to the book?

There are countless stories and details that I would have liked to include but left out for lack of space. I think what Czech readers may notice is that some of the very greatest jockeys associated with the Velká pardubická – Josef Váňa, for example – barely feature, whereas one or two English jockeys who Czechs may never have heard of get several paragraphs each. I’m afraid that this is just an inevitable side-effect of the book being written by an English author for, in the first instance, English readers. But I think the effects of this bias are very minor. Most of the riders I mention are there for good reasons – for example, because they rode against Lata, or because, like her, they are women who rode in the Velká pardubická.

You have explored the Velká pardubická. Would you say that you now know why it is such a huge phenomenon?

I think it’s a bit like our Grand National. The whole charm of it is that we can barely say why we like it. We like it because it’s a bit mad, and foreigners wouldn’t understand it, and it just happens to be part of the cultural and sporting fabric of British life. I’m sure Czechs feel much the same about the Velká pardubická. In both cases, we can see that, if you were designing a big national steeplechase from scratch, you wouldn’t make it like that, because it wouldn’t be sensible. But we love it because that’s the way it’s always been. It’s part of who we are, and we celebrate it an expression of our national character and heritage rather than as a rarefied contest of sport.

The Velká has many big fans in Britain, but it is also regarded as a very strange race. Have you come to any general conclusion about what the Brits think about the Velká?

We probably mythologise it more than you do: some people talk about it as a race that no one would ride in if they didn’t have several screws loose. It’s certainly seen as more extreme than anything in British racing – even though in some respects it’s arguably less extreme than the Grand National. I think we like the idea that, although we think of ourselves as being tough, the Czechs are actually much tougher than us, because they’re completely crazy. We mean that as a compliment, by the way.

How long did you spend researching in the Czech Republic, and what were the main difficulties for you?

The entire process of researching and writing took about two years, interspersed with other work. I think I spent about two months working on it in the Czech Republic, spread out over eight visits. But most of the work I did from the UK. Some things, such as the language barrier, were much less of a problem than I had expected. The kindness and enthusiasm with which Czech people responded to my enquiries more than made up for any difficulties of comprehension. The main problem was simply that Lata lived a very long time ago, and for parts of her early life there is barely any surviving evidence at all. The printed archives of Czech horseracing in the 1920s and 1930s are, as you know, full of holes. And whereas with Emil Zátopek I was able to talk to large numbers of people who knew him well, in his prime, and were still alive, Lata was born 27 years earlier and had her finest sporting hour 15 years earlier. So the number of surviving eye-witnesses is that much smaller. I hope that I found all the evidence that was there to be found. But some episodes in her life remain a tantalising mystery, as readers will discover.

Has anything important changed in your perspective about Lata Brandisová, now that you have finished the book?

Probably not. I think when I started out, I imagined – as biographers probably always do – that I would find out every last detail of everything she had ever done, said or thought at every stage of her life. In fact, there are many aspects of her and her life that remain a mystery to me, even now. Perhaps most biographers end up feeling that, as well.

But there was one aspect of her wider story that I hadn’t been expecting at all when I first began my research, and that was the extent to which the most important races of her life were against active, hard-core, Nazi paramilitaries: SS officers and “brownshirts”. I don’t think anyone has ever looked at this before. But it gives a whole extra layer of significance to her achievements – which were pretty significant anyway.

If someone were to ask you: What did Lata achieve, what would you answer? Is it similar to the achievements of the big lady jockeys of today, for example Lizzie Kelly? Or is it more, is it less... Does her achievement reach beyond the small world of horse racing in some sense?

It’s very hard to compare the sporting achievements of one era with those of another. I suspect that, in purely sporting terms, Lata may not have been the greatest female steeplechase jockey who ever lived. The horses she rode in Pardubice were always pretty good ones, and it’s hard to know how much value, if any, she added. I think her achievements are better understood in sporting terms. She had the courage to ride in the Velká pardubická at a time when most people thought that, for a woman, it was almost suicidally dangerous to do so. She had the guts to insist on riding in the face of furious opposition. She had the toughness to remount again and again after painful falls, without losing her nerve or her will to win. And she had the inner firmness to ride with her nation’s hopes on her shoulders, at a crucial point in its history, and to humiliate Nazi Germany’s toughest and most intimidating jockeys. I suppose those are all sporting achievements. But they are also human achievements. She was the first and only woman to win Europe’s toughest steeplechase. That’s an achievement that echoes through the ages, far beyond the narrow world of steeplechasing.